News

Case Parrillo v. Italy

Published on: 09/09/2015

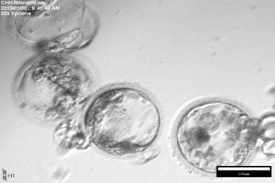

In 2002 Ms Parrillo and her partner had recourse to assisted reproduction techniques and underwent in vitro fertilisation treatment (hereafter “IVF”). Five embryos were obtained, and were stored by cryopreservation.

In 2002 Ms Parrillo and her partner had recourse to assisted reproduction techniques and underwent in vitro fertilisation treatment (hereafter “IVF”). Five embryos were obtained, and were stored by cryopreservation.Ms Parrillo’s partner died in November 2003, before the embryos could be implanted. After deciding not to go ahead with a pregnancy, she sought to donate them to scientific research and thus contribute to finding ways of curing diseases that are difficult to cure. However, section 13 of Law no. 40/2004 of 19 February 2004 prohibits experiments on human embryos, even for the purposes of scientific research, making any such experiment punishable by a sentence of between two and six years’ imprisonment. Ms Parrillo’s requests for the release of her embryos for this purpose were therefore refused. She submitted that the embryos in question had been obtained before Law no. 40/2004 entered into force and considered, in consequence, that it had been entirely legal for her to have them preserved rather than proceeding with immediate implantation.

Under Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 (protection of property), Ms Parrillo complained that she was unable to donate her embryos, conceived through medically assisted reproduction, to scientific research and was obliged to keep them in a state of cryopreservation until their death. Ms Parrillo also considered that the prohibition in question amounted to a violation of her right to respect for her private life, protected by Article 8.

The application was lodged with the European Court of Human Rights on 26 July 2011. On 28 May 2013 Ms Parrillo’s complaint under Article 10 (freedom of expression) – that the prohibition on embryo donation in question amounted to a breach of freedom of expression, a fundamental aspect of which was freedom of scientific research – was declared inadmissible, since it concerned a right which was not vested in the applicant directly, but rather in researchers and scientists.

On 28 January 2014 the Chamber to which the case had been assigned relinquished jurisdiction in favour of the Grand Chamber. A hearing took place in Strasbourg on 18 June 2014.

Decision of the Court

Admissibility – exhaustion of domestic remedies

The Italian Government alleged that Ms Parrillo ought to have used a remedy providing for a review of constitutionality, which was introduced in Italy in 2007. The Court welcomed, in this new form of review, the encouragement given by the Constitutional Court to the national judicial authorities to interpret domestic standards and the Constitution in the light of the European Convention on Human Rights and the Court’s case-law. However, it noted, on the one hand, that the Italian system provided only for indirect application by individuals to the Constitutional Court and, on the other, that it had not been shown, through established case-law and practice, that, where the donation of embryos to research was concerned, an action by Ms Parrillo before the ordinary courts to raise a question of constitutionality before the Constitutional Court in the light of the Convention would have amounted to an effective remedy. In consequence, it could not be claimed that Ms Parrillo ought to have exhausted this remedy.

On the applicability of Article 8 and the admissibility of Ms Parrillo’s complaint

For the first time, the Court was called upon to rule on the question whether the “right to respect for private life” could encompass the right to make use of embryos obtained from IVF for the purposes of donating them to scientific research. The “family life” aspect of Article 8 was not in issue here, since Ms Parrillo had chosen not to go ahead with a pregnancy with the embryos in question.

The Court, noting that the embryos obtained through IVF contained the genetic material of the person in question and accordingly represented a constituent part of his or her identity, concluded that Ms Parrillo’s ability to exercise a choice regarding the fate of her embryos concerned an intimate aspect of her personal life and accordingly related to her right to self-determination. The Court also took into account the importance attached by the domestic legal system to the freedom of choice of parents regarding the fate of embryos not destined for implantation. It therefore concluded that Article 8 was applicable in this case.

On the legitimacy of the aim pursued by the interference in Ms Parrillo’s private life

The ban on donating to scientific research embryos obtained from IVF that were not destined for implantation constituted an interference with Ms Parrillo’s right to respect for her private life, especially as the donation of embryos was not regulated in Italy at the time when she had had recourse to that reproductive technique. According to the Government, this interference, provided for in Law no. 40/2004, pursued the aim of protecting the “embryo’s potential for life”, as the human embryo is considered in the Italian legal system as a subject of law entitled to the respect due to human dignity. Although this aim could be linked to the legitimate aim of “protecting morals and the rights and freedoms of others”, as provided for in Article 8, this did not imply any assessment by the Court as to whether the word “others” extended to human embryos.

Necessity of the interference in a democratic society

The Court considered at the outset that Italy was to be afforded a wide margin of appreciation in this case, which raised sensitive moral and ethical issues. In addition, it did not concern prospective parenthood, and the right invoked by Ms Parrillo was not one of the core rights protected by Article 8, as it did not concern a crucial aspect of her existence and identity. This need for a wide margin of appreciation was confirmed, firstly, by the lack of a European consensus on this subject and, secondly, by the international texts.

The Court noted that there was no European consensus on the delicate question of the donation of embryos not destined for implantation. Although certain member States had adopted a permissive approach in this area (17 countries out of 41), others had chosen to prohibit it (Andorra, Latvia, Croatia and Malta) or to impose strict conditions on research using embryonic cells (for example, Slovakia, Germany, Austria or Italy).

With regard to the international texts, the relevant Council of Europe and European Union materials confirmed that the domestic authorities enjoyed a broad margin of discretion to enact restrictive legislation where the destruction of human embryos was at stake, having regard, among other things, to the plurality of views in Europe on the concept of the beginning of human life. While certain limits were imposed at European level, these aimed rather to temper excesses in this area.

With regard to the Italian legislation on this matter, the Court noted, firstly, that the drafting of Law no. 40/2004 had given rise to considerable discussions and that the Italian legislature had taken account of the State’s interest in protecting the embryo and that of the persons concerned in exercising their right to individual self-determination, and, secondly, that the inconsistencies in Italian law alleged by Ms Parrillo – on account, she submitted, of the right to abortion in Italy and the use by Italian researchers of embryonic cell lines taken from embryos that had been destroyed abroad – did not directly affect the right invoked by her.

Lastly, the Court noted that there was no evidence that Ms Parrillo’s deceased partner, who had had the same interest in the embryos in question as the applicant at the time of the IVF, would have wished to give the embryos to science. Moreover, there were no regulations governing this situation in Italy.

The Court concluded that Italy had not overstepped the wide margin of appreciation enjoyed by it in this case and that the ban in question had been “necessary in a democratic society”. In consequence, there had been no violation of Article 8.

The Court considered that it was not necessary to examine the sensitive and controversial question of the status of the human embryo in vitro and when human life begins, given that Article 2 (right to life) was not in issue in this case. With regard to Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 (protection of property), the Court considered that it did not apply to the present case, since human embryos could not be reduced to “possessions” within the meaning of that provision. This complaint was accordingly dismissed.

- Published on: 28/06/2016

- Gov. John Bel Edwards has reversed course from his predecessor and agreed to create regulations governing surrogacy births in Louisiana. Read more

- Published on: 18/05/2016

- Experts point out that serious questions are raised regarding the birth of a child by an elderly woman Read more

- Published on: 18/05/2016

- A controversial geneticist, Severino Antinori, who became known for helping women over 60 years old to become pregnant, was arrested for stealing eggs from a patient. Read more